BBC 100件藏品中的世界史008:Egyptian Painted Pottery Cattle埃及彩绘陶牛

008:Episode 8 - Egyptian Painted Pottery Cattle

第八集——埃及彩绘陶牛

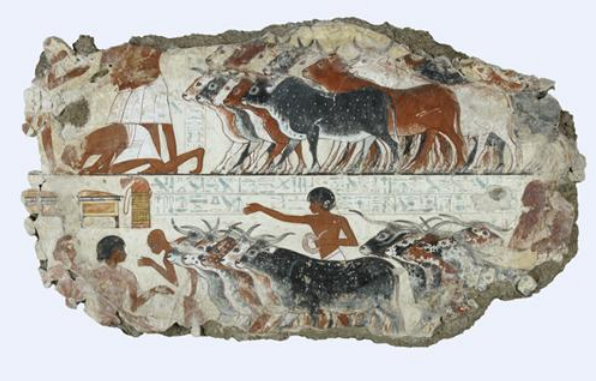

Model of four cattle (made around 5,500 years ago). Painted clay, found at El Amra, southern Egypt

四牛模型,彩绘泥塑,距今约五千五百年前,出土于埃及南部El Amra地区。

Mention excavation in Egypt, and most of us immediately see ourselves entering Tutankhamun's tomb, discovering the hidden treasures of the pharaohs and at a stroke rewriting history. Aspiring archaeologists should be warned that this happens only very rarely.

提及在埃及的考古挖掘,我们绝大多数人自然而然地就联想到进入图坦卡蒙的法老陵墓,挖出隐藏多年的法老大宝藏,于是乎,一夜改写世界历史,一举成名天下名。可别说我要打击那些胸怀抱负、满腔热情的未来考古学家啊,事实上这种情况是极少发生的。

Most archaeology is of course a slow dirty business, followed by even slower recording of what has been found. And the tone of archaeological reports has a deliberate, academic, almost clerical dryness, far removed from the riotous swagger of Indiana Jones.

大多数的考古工作真是又累又苦,又慢又脏;逐一记录下发掘出来的有用没用的物品的过程,就更别提有多缓慢了。而且考古报告的基调几乎千篇一律的学术味十足、几乎是文书干燥的调调,与大家印象中“守宝奇兵”的缤纷招摇可是相去甚远。

In 1900, a member of the Egypt Exploration Society excavated a grave in southern Egypt. He soberly named his discovery Grave A23 and noted the contents:

1900年,埃及探索学会的某一成员在埃及南部发掘处一处墓葬,他正而八经地将这发现命名为墓A23,并记录其中发现成果如下:

'Body, male. Baton of clay painted in red stripes, with imitation mace-head of clay. Small red pottery box, four-sided, 9 inches x 6 inches. Leg bones of small animal. Pots and - stand of 4 clay cows.'

“遗体,男性。泥塑棍棒,表面涂有红色条纹,顶端是仿狼牙棒头。方型小陶盒,四面9英寸x 6英寸,内装:小动物脚骨。陶罐若干,站立式四牛泥塑模型一件。”

These four little clay cows are a long way from the glamour of the pharaohs, but you could argue that cows and what they represent have been far more important to human history. Babies have been reared on their milk, temples have been built to them, whole societies have been fed by them, economies have been built on them. Without cows there are no cowboys, and without cowboys no Wild West. Our world would have been a different and a duller place without the cow.

当年这四只小小的陶牛与法老们辉煌与伟大真是无从相比,然而你也可以这么说,这些陶牛及其代表的意义在人类历史上可以占有更加重要的地位。人类的婴儿喝着牛奶成长,人类建立起供奉牛的神庙。没有牛就没有牛仔,没有牛仔就没有美国的狂野西部文化。假如没有牛的存在,我们的世界将会变得多么的不同与乏味啊。

'They were a very important part of the Egyptian economy. It became essentially a symbol for life.' (Professor Fekri Hassan)

“它们是古埃及经济相当重要的一部分,牛在本质上已经成为一种生命的象征。” 法克瑞·哈桑教授说道。

'It's not that easy for archaeologists to pin down how food processing worked in these early stages, but some of these artefacts can give us a good insight into it.' (Professor Martin Jones)

“对于考古学家来说,精确地找出在这些人类早期阶段食品加工究竟是怎么样的,可不是一件轻松活;不过有些文物可以给我们提供一向很好的启示。”马丁·琼斯教授说道。

Four horned cows stand side by side upon fertile land. And indeed they've been grazing on their little patch of grass for about five and a half thousand years. They're ancient Egyptian, more ancient even than the pharaohs or the pyramids.

这四只带角的牛肩并肩站成在肥沃的土地上,它们就在那块小草地上吃草,渡过了五千五百年的漫长岁月。它们来自古埃及,甚至比古法老金字塔的年代还要久

These cows are miniatures - small models, hand-moulded out of a single lump of Nile river clay. And on them you can still see very faint traces of black-and-white paint applied after the clay had been lightly baked.

这四只牛是实物小缩影,或者说是小模型,一次性手工造模成型,材料是一小块尼罗河粘土。在它们身上,当初粘土微火烘培后所涂上的黑白涂料仍旧留有隐隐约约的痕迹。

Like toy farm-animals of the sort most of us played with as children, they stand only a few inches high, and the clay base that they share is roughly the size of a dinner plate. These cows were buried with a man in a cemetery near a small village near El Amra in southern Egypt.

就像我们当小孩时玩的玩具农场动物一样,这些陶牛模型站着有几英寸高,托着它们的粘土盘也就餐盘大小。这些陶牛是一个男性的随葬品,地置大概在南部埃及靠近El Amra地区的小村落附近。

Like all the objects I've chosen this week, these creatures speak of the consequences of climate change and human responses to it. They have a story to tell about their owner that stretches far beyond Grave A23.

就像本周我选择的其他物品一样,这些陶牛也描述了气候变化和对人类生活产生的相关影响。它们拥有自己的故事,远远超越了这处命名为墓A23的墓葬地。

All of the things found in this grave were intended to be useful in another world and, in a way never imagined by the people who placed them there, they are. But they're useful for us, not for the dead. Because they allow us unique insights into remote societies, their way of death casting light on their way of life, and perhaps even more important, they give us some idea not just of what people did but of what they thought and believed.

这座坟墓中出土的一切物品,当初为了以供墓主来生使用;如今它们的有用之处,却是当年人们放置物品时绝对想象不到的。因为它们是对我们这些活着的人有用,而不是那些死去的前人。因为它们为我们了解那遥远的人类早期社会提供了独特的见解,他们的死亡方式恰恰折射出他们当初的生活方式。也许更重要的是,这些随葬品让我们了解到的,不止是当时人们做了什么,还有他们在想什么,相信什么。

Most of what we know about early Egypt, that's Egypt before the pharaohs and the hieroglyphs, is based on burial objects that archaeologists have discovered, objects like these little cows. They come from a time when Egypt was populated only by small farming communities living along the Nile Valley.

早期古埃及是指埃及法老与象形文字出现之前的年代,通常现在我们对那段时期的了解,大部分都来自于这些类似这些小陶牛的考古发掘成果。它们所处的那个年代,古埃及人类们还只是形成规模不大的农耕小村落,零星地散布在尼河罗谷上。

Compared to the spectacular gold and tomb ornaments of later Egypt, these little clay cows are a modest thing. Funerals at that point were simpler; they didn't involve embalming or mummifying; that kind of practice wouldn't come for another thousand years. Instead we find a simpler way of burying people.

与古埃及晚期壮丽辉煌的黄金与墓饰相比,这些小小的陶牛真是登不上大雅之堂。然而在这个时期,墓葬礼仪通常相对简单,没有涉及到防腐处理或者木乃伊化,这两种习俗还要晚一千年才出现。相对的,根据我们所发现的,当时采用了一种更简单的方式来埋葬死者。

The owner of our four clay cows would have been laid in an oval pit. He would have been placed in a crouched position, lying on a mat of rushes, facing the setting sun. And around him were his grave goods - items of value for his journey into the afterlife, five and a half thousand years ago; among them his four clay cows. Cow models like this one are quite common, so we can be fairly sure that cows must have played a significant part in Egyptian daily life - such an important part, in fact, that they couldn't be left behind when the owner passed through death and on into the afterlife. How did this humble beast become so important to human beings? Martin Jones, Professor of Archaeological Science at Cambridge University, is an expert in the archaeology of food:

我们这些小陶牛的墓主被长眠着一座椭圆型的土坑里。他被放置成为蜷缩的姿势,躺在一张蒲草垫上,面向落日的方向。他身边环绕着他的随葬品,都是一些在他踏上来生旅程上可以用到的物品,而这些掩埋在五千五百年岁月尘埃中的物品,就包括他的四只小陶牛。类似的陶牛模型在那时的埃及相当普遍,所以我们可以肯定牛在当时人类日常生活发挥了相当重要的作用。作用性大到,即使主人的死亡也不能使他与他的牛群分开,要一同带往来生。那么这种不起眼的牲畜是如何变得对人类如此重要的呢?剑桥大学的考古学教授马丁·琼斯是食物考古专家:

'If we think of the human diet in two steps - one is with early modern humans, there is an enormous adventurous diversification. We were eating everything - seeds, fish, mammoths, birds - anything that moves we are finding a way to eat it. And then there is a second episode, which starts around ten thousand years ago, where we seem to home in on a small number of target species, particularly grass seeds (what we call cereals), underground tubers, and a small number of animals.'

“如果我们把人类饮食分成两个阶段,第一阶段便是早期现代人种,当时人类的饮食范围真是一种庞大而冒险的多样化。几乎什么东西都吃——种子、鱼、猛犸象、鸟类等等。只要那东西会动,我们就会想方设法抓来吃。然后第二阶段,大概开始于一万年前左右, 我们开始把注意力集中在种类相对较少的食物品种上,最多的是草籽,或者我们所说的谷物,地下块茎,还有就是极少数的动物。

The story begins over nine thousand years ago, in the vast expanses of the Sahara. In Egypt then, instead of today's landscape of arid desert, the Sahara was a lush, open savannah with gazelles, giraffes, zebras, elephant and wild cattle roaming through it - happy hunting for humans.

故事大概开始于九千年前左右,在撒哈拉那广袤无垠的土地上。然而当年的埃及,可不是如今这般干旱荒凉的沙漠景观,那年的撒哈拉一派郁郁葱葱、草水丰盛、一望无际的热带稀树大草原,羚羊、长颈鹿、斑马、大象和野牛等动物就在这片沃土上生息繁衍——对人类而言,这却是一片狩猎的沃土了。

But around eight thousand years ago, the rains that nourished this landscape dried up. Without rain, the land began to turn to the desert that we know today, leaving people and animals to seek ever-dwindling sources of water. This dramatic change of environment meant that people had to find an alternative to hunting.

然后大概在八千元前左右,曾经滋养着这方水土的雨水突然干涸。没有了雨水,土地开始沙化,逐渐演变成我们今天所熟悉的大沙漠,迫使人类与动物背井离乡,到处寻找日益减少的水源。这种戏剧性的剧烈环境变化,意味着人们不得不寻找一种方式来代替狩猎。

Somehow they found a way to tame wild cattle. No longer did they just chase them, one by one, they learnt how to gather and manage herds, with which they travelled and from which they could live. Cows became almost literally the lifeblood of these new communities. The needs of fresh water and pasture for the cattle now determined the very rhythm of life as both human and animal activity became ever more intertwined.

也不知如何,他们寻找到了一种方法来驯服野牛。人类不再逐一地追逐着野牛,而是学会了如何集合它们,如何驯化它们。人类在迁徙的过程中带上了牛群,人类依靠着牛群而生存。牛群于是渐渐变成了这种新兴人类群体的生命线。随着人类与牛群彼此互动变得越来越相互交织,寻找牛群所需的新鲜水源与肥沃牧草开始变成人类生活的主旋律。

What role did these early Egyptian cattle play in this sort of society? What did they keep cows for? Professor Fekri Hassan has excavated and studied many of these early Egyptian graves:

那么在早期古埃及社会,牛群扮演了什么样的角色呢?人们养牛群在干什么?法克瑞·哈桑教授挖掘与研究过许多这些早期的古埃及坟墓:

'These people had farming villages, and I happen to have excavated sites in the Naqada region. And we found remains of animal enclosures, as well as evidence for the consumption of cattle. We found the bones of these animals. And these items, these models of cattle, were probably produced a millennium or more after cattle were introduced into Egypt.'

“这些人类生存在农耕村落里,我碰巧发掘过Naqada地区附近的考古遗址。我们发现了一些动物外壳遗骸,以及人类食用牛的证据。我们发掘了这些动物的骨头。这些物品,这些陶牛模型,可能大概出现在驯化牛被引进埃及的千年之后。”

Study of the bones of these cattle from ancient times shows the ages at which the animals were killed. Surprisingly, many of them were old, at least too old if they were being kept only for food. So unless the early Egyptians enjoyed very tough steak, these are not in our sense beef cattle.

对于这些远古时期驯化牛骨骼的研究结果告诉了我们这些家畜宰杀时的年龄。令人惊讶的是,其中大部分已经是老牛了,至少对于肉用牛而言,真是太过老了。因此除非三埃及人真的相当享受啃着又干又硬的老牛排,这些牛绝对不是我们印象中的肉用牛。

And they must have been kept alive for other reasons - perhaps to carry water or possessions on journeys. But it seems more likely they were tapped for blood which, if you drink it or add it to stews, gives you essential extra protein - it's something we find in many parts of the world, and it's still done today by the nomadic peoples in Kenya.

那么,它们肯定是人类为了其他目的而养育起来的。有可能是在人类迁徙过程中做些挑水或负重之类的工作吧。不过看上去似乎还有另一种可能性——人类的目的是牛血,例如直接饮用,或者添加到炖菜里头,可以补充额外的蛋白质。这种用途我们已经在世界上很多地区都发现了,而且如今肯尼亚的游牧人民仍旧这么做。

So are our four cows a walking blood bank? The more obvious answer, that they were dairy cows, we can probably rule out, because for several reasons milk was unfortunately off the menu. Not only did these early domesticated cows produce very little milk but, more importantly for humans, drinking cows' milk is very much an acquired skill. Martin Jones again:

这样说来我们那四只陶牛岂不是四只活动血库的缩影?奶牛这种更明显的答案我们大概已经可以排除,因为很不巧的基于若干原因,牛奶是上不了当时人类菜谱的了。首先这些早期驯化牛根本就产生不了多少牛奶,但最重要的仍是,对人类而言,喝牛奶其实是一种获得性的技能。马丁·琼斯再次说道:

'There are a range of other foods that our distant ancestors would not have eaten as readily as we do, something as commoplace as milk is something that we have had to evolve to tolerate, because milk is biologically designed just for very young mammals, and we needed to genetically evolve in order to tolerate drinking milk as adults, and indeed a great number of modern peoples around the world don't have that tolerance of drinking milk as adults.'

“有些品种的食物我们那些遥远的祖先消化吃来可不如我们一样的容易。像牛奶这样对我们再寻常不过的食物,人类当初不得不通过漫长的演化过程来适应。这是因为奶类从生物角度而言,就是专门作为非常年轻的哺乳类动物幼崽准备的。作为成人要适应喝奶,我们还需要从基因上进化。事实上现在世界各地还有相当部分的成年人类没有办法消化牛奶。”

So, drinking cows' milk would probably have made these early Egyptians very ill, but they and many other populations eventually adapted. We're not only what we eat, we are essentially what our ancestors - with great difficulty - 'learned' to eat.

因此,对当年的早期古埃及人,喝牛奶可能会让他们病得厉害。然而他们及其他地区的人类通过演化最终学会了适应。我们不仅仅是由我们吃的东西所决定,基本上我们就是由我们祖先克服重重困难,最终学会“吃”的成品。

But in early Egypt cows were probably also kept as a kind of insurance policy. If crops or the immediate surroundings were damaged by fire, communities could always fall back on the cow for nourishment as a last resort; perhaps not the best thing to eat, but always there. They were also socially and ceremonially significant but, as Fekri Hassan explains, their importance went even deeper:

不过早期古埃及,牛也可以被当成一种风险保障来饲养。假如作物失收或者遭遇了火灾之类的,人类村落最终总能把饲养的家牛当成最后的资源,可能不是最佳选择,但是最保险的选择。牛群还承载着重要的社会与礼仪上的意义。然而按照法克瑞·哈桑的解释,其重要性甚至更深:

'Cattle have always had religious significance, both the bulls and the cows; it's related mostly to life. In the desert a cow was the source of life. And we have many representations in rock art, where we see cows with their calves in a more-or-less a religious scene - and we also see human female figurines, also modelled from clay, with raised arms as if they were horns. So it seems to me that cattle were quite important in religious ideology.'

“牛一向具有宗教意义,无论是公牛还是母牛都一样;它主要涉及到生命。在沙漠里头,一头牛曾经是生命之源。我们可以在早期岩石艺术上找到很多的印证,看到许多母牛与它们的小牛出现在一些差不多是宗教场景中——同时我们还发现在女性人型俑,也是粘土模型,高高举起的双手就像是牛角。所以在我看来,这些牛群在古人类的宗教意识中地位相当重要。

The cattle in front of me don't show any outward signs of being particularly special. On closer inspection, however, they don't look like the cows you find on the farm today, anywhere across Europe, North America or the Middle East. Their horns are strikingly different - they curve forwards and much lower than any cows that we know, and that's because they're not like the cows that we know.

摆在我面前的这几只陶牛,乍一看外表上没啥出奇。然而一旦仔细观察,就可以看出它们长得跟我们现代欧洲、北美或者中东任何农场上的牛群一点都不像。它们的牛角极明显的不同。那牛角前弯的弧度很大,而且比我们所见过的任何牛都要低。其实这恰恰因为它们本不是我们如今所知道的家养牛。

All the cows alive in the world today descend from Asia. Our Egyptian model cows look different from the ones we know today because they were descended from native African cattle, which have now become extinct.

现代存活的所有家养牛都是亚洲牛的后代。我们这些早期古埃及的陶牛模型看起来与我们所熟悉的牛不一样,是因为它们是非洲本土原生牛,早就已经灭绝了。

Along the Nile Valley, the cow eventually transformed human existence, and in fact became so much a central part of the Egyptian world that it even inspired worship. We all need our gods to be close to what we eat.

悠悠岁月的尼罗河流域,牛群最终改变了人类的生存方式,事实上也构成了古埃及世界的中央部分,甚至引发了人类对它们的宗拜意识。我们都需要我们的神在某种意义上接近我们的食物。

Whether this cow worship started as early as the time of our little model cows is still a matter of debate, but in later Egyptian mythology the cow takes on a prominent role in religion, worshipped as the powerful cow goddess Bat.

是否最初的牛崇拜出现于我们这小陶牛模型制造出来的时代,这问题还在争议中,然而更晚期的埃及神话中,牛在宗教中起了很突出的作用,被当成强大的牛女神Bat来崇拜。

She is typically shown with the face of a woman and the ears and horns of a cow. And we can see just how far cattle have gained in status, by the fact that subsequently, Egyptian kings were honoured with the title Bull of his Mother - the cow had come to be seen as the creator of the pharaohs.

她通常是拥有女性的脸孔及牛耳和牛角。随后历史中,牛的地位更是得以大大提升,埃及法老通常加上“他母亲的公牛”这样的称号——牛甚至成为法老的创造者。

In the next programme, I'm moving from cows to corn - but I'm staying with the gods - this time, the all-powerful god of maize, in Mexico.

在接下来的节目里,我将把注意力从牛身上转移到玉米上,然而依靠与神相伴。这次我要介绍的是在墨西哥,那全能的玉米之神。