旅行的艺术:风景 Ⅴ 乡村与城市-6

6

6

为什么?为什么接近一座瀑布、一座山或自然界中的任何一部分,一个人比较能免于“仇恨和卑劣欲望”的骚扰?为什么在比肩接踵的街道就做不到?

Why? Why would proximity to a cataract, a mountain or any other part of nature render one less likely to experience 'enmities and low desires' than proximity to crowded streets?

湖区提供了我们一些线索。我和M在这里的第一个早晨起得很早,到“凡人”旅馆的早点室享用早餐。它的墙漆上一层粉红色,从窗口向外望出,是一个茂密的山谷。外面下着大雨,但房东向我们保证,这不过是一场过路雨。他接着为我们呈上了粥,并提醒我们早餐若想加蛋必须额外付费。录音机正在播放秘鲁的管乐,并且穿插亨德尔 [7] 《弥赛亚》片断。我们用过早点后,把背包整理好,随即开车到安布赛德镇采购一些背包行走的必用品,如指南针、防水地图套、水、巧克力和三明治。

The Lake District offered suggestions. M and I rose early on our first morning and went down to the Mortal Man's breakfast room, which was painted pink and overlooked a luxuriant valley. It was raining heavily, but the landlord assured us, before serving us porridge and informing us that eggs would cost extra, that this was but a passing shower. A tape recorder was playing Peruvian pipe music, interspersed with highlights of Handel's Messiah. Having eaten, we packed a rucksack and drove to the town of Ambleside, where we bought a few items to take with us on a walk: a compass, a waterproof map holder, water, chocolate and some sandwiches.

安布赛德镇虽然不大,但是它却有大都会的喧哗。大卡车正在商店外卸货,嘈杂声不断。另外,到处都可看见餐馆和旅店的告示牌。虽然我们很早便到达这里,但茶室早已座无虚席。报摊架上的报纸,刊登了伦敦一场政治丑闻的最新态势。

Little, Ambleside had the bustle of a metropolis. Lorries were noisily unloading their goods outside shops, there were placards everywhere advertising restaurants and hotels, and though it was still early the teashops were full. On racks outside newsagents, the papers carried the latest development in a political scandal in London.

然而,安布赛德镇西北方几英里外的大朗戴尔谷,景色却迥然不同。我们自抵达湖区以来,首次深入乡间,感受到了大自然的气息远强于人气。行道两旁的田野里耸立着许多橡树,树与树之间都相隔一段距离,对山羊来说,这片田野肯定曾让它们胃口大开,因为整个的田野已被它们啃平,变成不错的草坪了。橡树长得非常高雅标致。它的树枝不像柳树那样垂卧在地上,叶子也不像一些白杨树那样不修边幅,近距离看起来像半夜被唤醒的模样一样:头发蓬乱、不及梳理。相比之下,橡树将低处的树枝紧密地收聚起来,较高处的树枝则有序地生长,形成了一个翠绿茂密、近乎完美的圆形冠顶,就好像小孩的画中树的原型一样。

A few miles north-west of the town, in the Great Langdale valley, the atmosphere was transformed. For the first time since arriving in the Lake District, we were in deep countryside, where nature was more in evidence than humans. On either side of the path stood a number of oak trees. Each one grew far from the shadow of its neighbour, in fields so appetizing to sheep as to have been eaten down to a perfect lawn. The oaks were of noble bearing: they did not trail their branches on the ground like willows, nor did their leaves have the dishevelled appearance of certain poplars, which can look from close-up as though they have been awoken in the middle of the night and not had time to fix their hair. Instead they gathered their lower branches tightly under themselves while their upper branches grew in small orderly steps, producing a rich green foliage in an almost perfect circle-like an archetypal tree drawn by a child.

与房东预测的相反,雨继续下个不停,站在橡树下,我们感觉到了橡树的硕大。雨点洒落在4万片树叶上,击打或大或小、或高或低、或积水或少水的叶片,发出了不同音调的声响,形成了“噼里啪啦”的和谐旋律。这些树木形成了一个复杂而又有序的系统:树根耐心地从泥土中吸收养分;树干中的毛细管将水和养分朝25米高的上方运送;每根树枝吸收足够的养分滋润树叶;每片树叶尽力为整棵树贡献一己之力。这些树木也体现出了耐心:它们耸立在这个下雨的早晨,不发一句怨言,只是适应着季节的缓慢转变。它们不会因为风狂雨暴而陷入狂躁,也不会因耐不住寂寞而想要远走高飞,去往别的河谷。这些橡树安安分分的,树根像细长的手指深入湿湿的土壤里,延伸到离主干若干米的地方,同时也远离了最高处蓄满雨水的树叶。

The rain, which continued to fall confidently despite the promises of the landlord, gave us a sense of the mass of the oaks. From under their damp canopy, rain could be heard falling on 40,000 leaves, creating a harmonious pitter-patter, varying in pitch according to whether water dripped on to a large or a small leaf, a high or a low one, one loaded with accumulated water or not. The trees were an image of ordered complexity: the roots patiently drew nutrients from the soil, the capillaries of their trunks sent water twenty-five metres upwards, each branch took enough but not too much for the needs of its own leaves, each leaf contributed to the maintenance of the whole. The trees were an image of patience too, for they would sit out this rainy morning and the many that would follow it without complaint, adjusting themselves to the slow shift of the seasons-showing no ill-temper in a storm, no desire to wander from their spot for an impetuous journey across to another valley; content to keep their many slender fingers deep in the clammy soil, metres from their central stems and far from the tallest leaves which held the rainwater in their palms.

华兹华斯喜欢坐在橡树下,聆听着雨声或者看着阳光穿梭于树叶间。他把树木的耐心和庄严看作是大自然特有的杰作,并且认为这些价值应该受到尊重。他写道:

Wordsworth enjoyed sitting beneath oaks, listening to the rain or watching sunbeams fracture across their leaves. What he saw as the patience and dignity of the trees struck him as characteristic of Nature's works, which were to be valued for holding up:

在心灵为了眼前的景物

before the mind intoxicate

沉醉之前,一场眼花缭乱之舞

With present objects, and the busy dance

转瞬即逝,大自然却适度呈现了

Of things that pass away, a temperate show

一些永恒的东西

Of objects that endure

华兹华斯说,大自然会指引我们从生命和彼此身上寻找“一切存在着的美好和善良的东西”,自然是“美好意念的影像”,对于扭曲、不正常的都市生活有矫正的功能。

Nature would, he proposed, dispose us to seek out in life and in each other, 'Whate'er there is desirable and good'. She was an 'image of right reason' that would temper the crooked impulses of urban life.

如果我们要接受华兹华斯的论点(即便是其中一部分),我们就必须接受以下前提:人的身份认同多多少少都具有伸缩性,也就是说,我们的个性会随着周围的人或物的转变而变化。与某些人往来,可能会激发我们的慷慨和敏感,但与另外一些人来往则会引发我们的好胜和嫉妒心。A君对于地位和权势的迷恋可能会悄悄引发B君对自己身份轻重的担忧。A君所开的玩笑可能潜移默化地激起B君隐藏在内心已久的荒谬感。但如果把B君置于另一个环境,他所关注的事物将受新的互动者的言行举止影响,随之发生转变。

To accept even in part Wordsworth's argument may require that we accept a prior principle: that our identities are to a greater or lesser extent malleable; that we change according to whom-and sometimes what -we are with. The company of certain people excites our generosity and sensitivity, of others, our competitiveness and envy. A's obsession with status and hierarchy may-almost imperceptibly-lead B to worry about his significance. A's jokes may quietly lend assistance to B's hitherto submerged sense of the ridiculous. But move B to another environment and his concerns will subtly shift in relation to a new interlocutor.

那么如果把人放置于大自然中,与一座瀑布或高山、一棵橡树或一株白屈菜共处,又会对他的身份认同产生什么影响呢?毕竟,草木无情,它们何以能鼓励我们,让我们从善如流。然而,华兹华斯坚持认为人类能从大自然中获益,其论点的关键在于:一个没有活动能力的物体仍然能对它周遭的事物产生影响。自然景物具有提示我们某些价值的能力,例如:橡树象征尊严、松树象征坚毅、湖泊象征静谧。因此,自然界景物能够含蓄地唤起我们的德性。

What may then be expected to occur to a person's identity in the company of a cataract or mountain, an oak tree or a celandine-objects which, after all, have no conscious concerns and so, it would seem, cannot either encourage or censor behaviour? And yet an inanimate object may, to come to the linchpin of Wordsworth's claim for the beneficial effects of nature, still work an influence on those around it. Natural scenes have the power to suggest certain values to us-oaks dignity, pines resolution, lakes calm-and, in unobtrusive ways, may therefore act as inspirations to virtue.

华兹华斯在1802年夏天写给一位年轻学生的信中,讨论了诗歌的作用。他在信中几乎明确指出自然界所包含的价值。他说:“一位伟大的诗人……应该在某种程度上矫正人们的思想感情……使他们的感情更健全、纯洁和永久,也就是与大自然产生共鸣、更加和谐。”

In a letter written to a young student in the summer of 1802, while discussing the task of poetry, Wordsworth came close to specifying the values he felt Nature embodied: 'A great Poet … ought to a certain degree to rectify men's feelings … to render their feelings more sane, pure and permanent, in short, more consonant to Nature.'

华兹华斯从每个自然景观中都能找到这份稳健、纯洁和永恒性。例如,花朵是谦卑和温顺的典范。

In every natural landscape, Wordsworth found instances of this sanity, purity and permanence. Flowers, for example, were models of humility and meekness.

致雏菊

TO THE DAISY

甜美、恬静的你!

Sweet silent Creature!

与我一同沐浴在阳光中、在空气中吐息

That breath'st with me in sun and air,

你以欢欣和柔顺

Do thou, as thou art wont, repair

温润

My heart with gladness, and a share

我的心

Of thy meek nature!

动物是坚忍的象征。华兹华斯对一只蓝色山雀特别钟爱,因为即使是最恶劣的天气,它也仍旧在诗人寓所“鸽舍”的果园里高歌一曲。诗人和妹妹多萝茜在那里度过的第一个严冬,便被一对天鹅感动,这对天鹅也是那里的新客,但却比他们兄妹俩更能忍耐寒冷。

Animals, for their part, were paragons of stoicism. Wordsworth at one point became quite attached to a bluetit that, even in the worst weather, sang in the orchard above Dove Cottage. During their first, freezing winter there, the poet and his sister were inspired by a pair of swans that were also new to the area and endured the cold with greater patience than the Wordsworths.

我们在朗戴尔山谷走了1个小时后,雨势开始减弱,我和M听见了持续不断但十分微弱的“啐”声,穿插着较强的“啼嗦”声。三只鹨从草丛中飞出,一只黑耳麦翁鸟则高踞在松树枝上,神色忧郁,它在夏末的阳光中晒着那沙黄色的羽毛。不知什么东西惊动了它,它突地飞离了原位,在山谷上空盘旋,并发出迅疾而刺耳的叫声:“嘘耳,嘘喂,嘘喂喔!”然而这阵鸣叫声却丝毫未对岩石上费力攀爬的毛毛虫产生影响,而谷地上的众多绵羊也无动于衷。

An hour up the Langdale valley, the rain having abated, M and I hear a faint tseep, rapidly repeated, alternating with a louder tissip. Three meadow pipits are flying out of a patch of rough grass. A black-eared wheatear is looking pensive on a conifer branch, warming its pale sandy-buff feathers in the late summer sun. Stirred by something, it takes off and circles the valley, releasing a rapid and high-pitched schwer, schwee, schweeoo . The sound has no effect on a caterpillar walking strenuously across a rock, nor on the many sheep dotted over the valley floor.

一只羊缓缓地走近小道,并好奇地望着游客。人和羊都惊讶地互相凝视。过了一阵,那只羊蹲了下来,懒洋洋地吃了一口草,好像在咀嚼口香糖一样。为什么我是我这样,而它又缘何是那般样子?另一只绵羊走过来,挨着它的同伴蹲了下来。霎时间里,它们好像交换了一个会意而欣然的眼神。

One of the sheep ambles towards the path and looks curiously at her visitors. Humans and sheep stare at one another in wonder. After a moment, the sheep sits down and takes a lazy mouthful of grass, chewing from the side of her mouth as though it was gum. Why am I me and she she? Another sheep approaches and lies next to her companion, wool to wool, and for a second they exchange what appears to be a knowing, mildly amused glance.

在前方几米处,有一片蔓延到溪流的草丛。草丛中突然发出一种奇怪的声音,像是一个倦意十足的老翁在饱食一餐后清理喉咙的声音。紧接着是杂乱的飒飒声,像是有人在一堆树叶中急躁不安地翻找宝物。一旦发现有来者,他便即刻安静下来,紧张得好像小孩在玩捉迷藏时躲在衣柜后面屏住呼吸,不敢出声。在安布赛德,人们买报纸,吃煎饼,而在这里,隐藏在草丛中的或许是一只长满毛、拖着一条尾巴、爱吃浆果和苍蝇的动物,正在树叶堆中乱窜,发出“呼噜,呼噜”的声音。然而,这个家伙尽管如此奇怪,却仍然活在当下,是个和我们一样睡觉和呼吸、活生生地生活在这个地球上的生物,而宇宙中除了这个星球有生物外,其他主要都是由岩石、蒸气和沉寂构成。

A few metres ahead, inside a deep green bush that grows down to a stream, comes a noise like that of a lethargic old man clearing his throat after a heavy lunch. This is followed by an incongruously frantic rustle, as though someone were rifling through a bed of leaves in an irritated search for a valuable possession. But on noticing that it has company, the creature falls silent, the tense silence of a child holding its breath at the back of a clothes cupboard during a game of hide-and-seek. In Ambleside, people are buying newspapers and eating scones. And here, buried in a bush, is a thing, probably with fur, perhaps a tail, interested in eating berries or flies, scurrying in the foliage, grunting-and yet still for all its oddities a contemporary, a fellow sleeping and breathing creature alive on this singular planet in a universe otherwise made up chiefly of rocks and vapours and silence.

华兹华斯写诗的目的之一是想引导我们去关注那些和我们生活在一起、却常被人漠视的动物。我们经常只是用眼角余光瞥它们一眼,从未尝试去了解它们正在做什么或想要什么,它们的存在不过是一些模糊而又普普通通的影子,例如尖塔上的小鸟和在草丛中穿梭的动物。诗人请读者放下他们的成见,设想用动物的眼光看看这个世界,并辗转切换于人类和自然界的视角。为什么这样做会有趣、甚至有启发性呢?也许不快乐的泉源正来自我们用单一的视角看世界。在我前往湖区的几天前,我发现有一本19世纪的书讨论华兹华斯对鸟类的兴趣。该书的序言中提示了运用多重视角看待事物的好处:

One of Wordsworth's poetic ambitions was to induce us to see the many animals living alongside us whom we typically ignore, registering them only out of the corner of our eyes, having no appreciation of what they are up to and want: shadowy, generic presences; the bird up on the steeple, the rustling creature in the bush. He invited his readers to abandon their usual perspectives and to consider for a time how the world might look through other eyes, to shuttle between the human and natural perspective. Why might this be interesting, or even inspiring? Perhaps because unhappiness can stem from having only one perspective to play with. A few days before travelling to the Lake District I had happened upon a nineteenth-century book that discussed Wordsworth's interest in birds and in its preface hinted at the benefits of the alternative perspective they offered:

我相信,如果这个国家的地方消息、每日新闻或一周大事不仅记载这块领土上伯爵、尊贵女士、国会议员和大人物的启程和返程,而且也记录鸟儿的抵达和离去,必定会给公众带来乐趣。

I am sure it would give much pleasure to many of the public if the local, daily and weekly press throughout this country would always record, not only the arrivals and departures of Lords, Ladies, MPs and the great people of this land, but also the arrivals and departures of birds.

如果我们对这个时代或精英的价值观感到痛心,那么思及地球生命的丰富多采,或许会让我们感到释然,让我们记住,这个世界除了大人物的事业,还有在原野鸣叫的草地鹨。

If we are pained by the values of the age or of the élite, it can be a source of relief to come upon reminders of the diversity of life on the planet, to hold in mind that, alongside the business of the great people of the land, there are also pipits tseeping in meadows.

当科尔律治回头看华兹华斯早期的诗作时,他认为这个天才作了以下的贡献:

Looking back on Wordsworth's early poems, Coleridge would assert that their genius had been to:

赋予日常事物以新意,并且激发一种类似超自然的感觉;通过唤醒人们的意识,使它从惯性的冷漠中解放出来,看着眼前的世界是多么可爱和奇妙。大自然是个取之不尽的宝藏,然而因为人类的惯性和自私自利的追逐,我们视而不见、充耳不闻,心灵既不能感受也不能领悟。

give the charm of novelty to things of every day, and to excite a feeling analogous to the supernatural, by awakening the mind's attention from the lethargy of custom, and directing it to the loveliness and wonders of the world before us; an inexhaustible treasure, but for which, in consequence of the film of familiarity and selfish solicitude we have eyes, yet see not, ears that hear not, and hearts that neither feel nor understand.

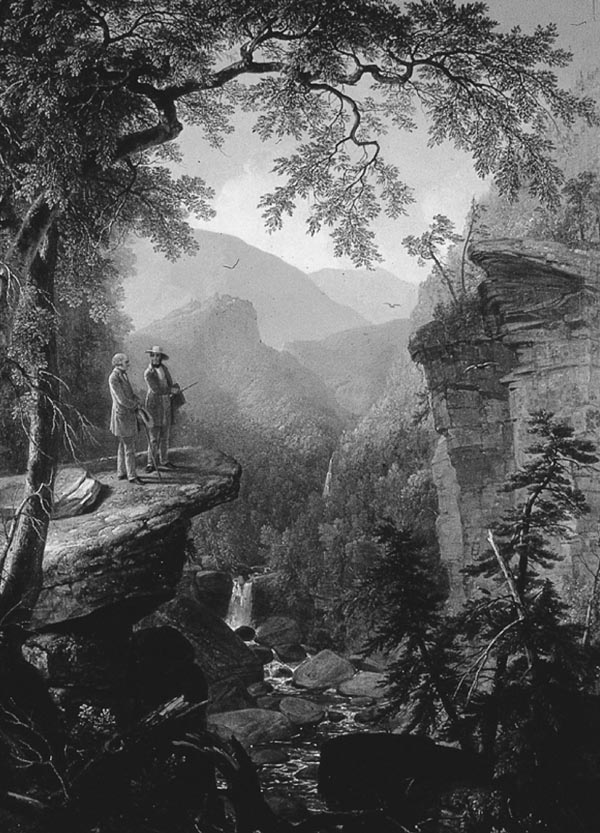

华兹华斯认为大自然的“可爱”能继而鼓励人们找到自己内在的善。两个人站在岩石边,俯瞰着河流及树木茂密的大山谷。这样的景色可能不仅改变了他们与自然的关系,也使得这两人之间的关系更不一样了。

Nature's 'loveliness' might in turn, according to Wordsworth, encourage us to locate the good in ourselves. Two people standing on the edge of a rock overlooking a stream and a grand wooded valley might transform their relationship not just with nature but, as significantly, with each other.

在悬崖相伴之下,我们曾关注的一些东西都显得不重要了。反之,一些崇高的念头油然而生。它的雄伟鼓励我们要稳重和宽宏大量;它的巨大体积教导我们用谦卑和善意尊重超越我们的东西。当然,站在一座瀑布前或许会引发我们对一位同事的羡慕,但是如果华兹华斯的观点能让人信服的话,那么出现这种情况的可能性会小一些。诗人认为人的一生如果在大自然中度过,人的性格会被改变不少,不再会争强好胜,羡慕别人,也不再焦虑,于是他欢呼:

There are concerns that seem indecent when one is in the company of a cliff; others to which cliffs naturally lend their assistance, their majesty encouraging the steady and highminded in ourselves, their size teaching us to respect with good grace and an awed humility all that surpasses us. It is of course still possible to feel envy for a colleague before a mighty cataract. It is just, if the Wordsworthian message is to be believed, a little more unlikely. Wordsworth argued that, through a life spent in nature, his character had been shaped to resist competition, envy and anxiety-and so he celebrated,

阿舍·布朗·杜兰德:《相近的灵魂》,1849年

… that first I looked

……起初

At Man through objects that were great or fair;

我透过伟大或美好的东西来看人,

First communed with him by their help. And thus

藉由这些东西的助力来深入了解人

Was founded a sure safeguard and defence

结果发现了一个稳固的堡垒,对抗

Against the weight of meanness, selfish cares,

卑鄙、自私、粗野、低俗——

Coarse manners, vulgar passions, that beat in

这些在我们日常生活世界

On all sides from the ordinary world

从四面八方向我们进袭的敌人。

In which we traffic

- 频道推荐

- |

- 全站推荐

- 推荐下载

- 网站推荐